Former Alcoa CEO & Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill,

July 21, 2011 Podcast, Mark Graban’s Lean Blog

When it comes to using risk management to advance the cause of institutional learning, Paul O’Neill, former chairman of Alcoa and Rand Corporation and the 72nd US Secretary of Treasury, has few peers. This is Paul’s story as he shared with us and a small group of business leaders in the summer of 2017 and it is memorialized in chapter four of Charles Duhigg’s book entitled The Power of Habit (2012).

In 1987 when O’Neill became the new CEO, Alcoa, a century-old company, had grown stodgy, profits had declined, and investors were unhappy about recent management missteps, including straying too far from the core business of manufacturing aluminum products. Not only was there growing dissatisfaction in the boardroom and on Wall Street, but the rank and file were also unhappy. For example, in response to improvements mandated by O’Neill’s predecessor, 15,000 Alcoa employees had gone on strike. Things were so bad that employees were dressing dummies as managers and burning them in effigy causing one observer to remark “Alcoa was not a happy family. It was more like the Manson family, but with the addition of molten metal.”

O’Neill’s life experience (born into a military family (son of an Army sergeant), public university education, and government experience in analyzing and improving operations) led him to develop a mental model of leadership that works constantly to develop a culture of teaching and learning. That is, he believed that he must work to change things daily until every Alcoa employee could answer affirmatively to these three inquiries on a daily basis:

- I am treated with dignity and respect by those that I encounter every day, regardless of gender, race, title, religion or level of education.

- I am given the things I need (training, education, equipment, support, etc.) so I can make a contribution to this organization that brings meaning to my life.

- I’m recognized every day for what I do by someone whose judgement I value.

O’Neill also realized that unless this type of culture existed, he would not be able to fulfill his desire to set organizational goals that are at the known level of possibility and to help everyone acquire and practice the skills necessary to achieve these goals. In short, O’Neill wanted to help the Alcoa workforce develop habits of excellence.

The challenge for O’Neill was that he had inherited an organization in which his mental model of leadership and institutional learning was not the norm. In fact, the century old company still reflected many of the outdated assumptions about leadership that were starting to be questioned by landmark management books such as Douglas McGregor’s The Human Side of Enterprise (1960).

Published at the start of O’Neill’s career, McGregor’s book confirmed a new model of leadership reflected in the beliefs and values that O’Neill would acquire through his own personal experience:

- Contrary to conventional thinking, people do not have an inherent dislike for work – with good leadership, employees derive satisfaction from their jobs.

- You don’t need to threaten your employees – properly motivated employees will perform on their own and will strive to meet organizational objectives.

- People enjoy the feeling of accomplishment – self-satisfaction through achievement reinforces employees’ commitment to organizational objectives.

- People want to be accountable – people are not inherently lazy. Instead, they actually seek responsibility.

- People are naturally creative – given the opportunity, most people are resourceful and imaginative. They can solve organizational problems.

- People are smart – too often, management badly underutilizes the collective intelligence of the workforce.

The lesson in O’Neill’s story is that risk management is about leadership and that the leader’s primary responsibility is to ensure the creation of an institutional learning system that produces a culture of habitual excellence. O’Neill explained:

“I knew I had to transform Alcoa. But you can't order people to change. That’s not how the brain works. So I decided I was going to start by focusing on one thing. If I could start disrupting the habits around one thing, it would spread throughout the entire company."

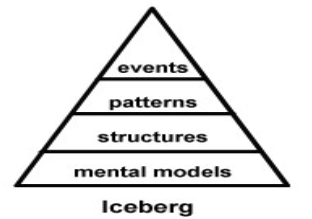

In our next column, we will take a deeper dive into O’Neill’s strategy and how it caused others in Alcoa (from the board to junior employees) to change their mental models, the structure of their workplace relationships, and ultimately their behaviors (patterns), which, in turn, led to record levels of prosperity (events). See iceberg model below.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed