Part II of our Conversation with Kevin Knight provides an inside look at how Australia and New Zealand developed the first standard for enterprise risk management known as AS/NZS 4360.

I was most fortunate that my employer encouraged me to become active in ARIMA, (the Association of Risk and Insurance Managers of Australia) as part of my professional development. This blessing put me in a position to respond to an enquiry that Standards Australia sent to a range of government, academic and professional bodies in our country about the feasibility of developing a standard on risk management for use in Australia and New Zealand, and the availability of volunteers willing and able to do the work. I was nominated as one of ARIMA’s representatives.

Having started out on the journey of standardization of risk management, I found myself getting further involved in the development of handbooks and revisions of AS/NZS 4360, which, in turn led to becoming involved with ISO, the International Organization for Standardization. It is fair to say I never expected to set out on what is to date a 27-year journey looking for a destination. 2020 should see me reach that destination and my retirement from all standards related activities.

You were an original member of the Joint Technical Committee (OB/7) which first met in August 1993 and published the first standard for risk management – AS/NZS 4360 – in November 1995. Who were the key individuals and organizations that influenced the development of AS/NZS 4360?

I have gone back to our records and they show that an enquiry from Standards Australia was received in May 1993. The enquiry enclosed terms of reference and suggestions on how to form our Joint Technical Committee which became known as OB/7. The minutes from nine meetings held between August 1993 and July 1994, show that our committee had representation from the following organizations:

- The Association of Risk & Insurance Managers of Australia

- The Australian Institute of Risk Managers

- Australia’s Department of Defence

- Department of Safety Science, University of New South Wales (NSW)

- NSW Department of Treasury - Infrastructure Development &

- Management Group

- Insurance Council of Australia

- Australia’s Department of Administrative Services

- Australian Computer Society

- Institution of Engineers of Australia

- Securities Institute of Australia

- Standards New Zealand

- Standards Australia

- National Insurance Brokers Association of Australia

- New South Wales Department of Planning

- Australian Customs Service

- Lincoln University of New Zealand

As evidenced by the above list, OB/7 had a diverse range of members who brought a wide set of knowledge, skills and experience to the meetings – all of which helped us create a generic process for risk management for a wide variety of purposes, including creating an ERM framework. It also ensured that the end result could be used by people with little formal knowledge or experience in risk management as opposed to becoming a tool that could only be used by people deemed to have expertise in some aspect of risk management. As such, we started out with a blank canvas. We were fortunate that several committee members had experience in legislative drafting which meant they knew how to develop a general idea into an Act of Parliament – a process similar to creating a standard.

Our Committee gathered the available information on risk management. All information, submissions and documents were copied and shared with committee members. After going through several drafts of a standard, the Committee made enough progress to seek public comment. To ensure maximum exposure, the representative organizations on the Committee were asked to encourage responses from their membership, advertisements were placed in the daily press seeking input from the general public, and copies were supplied to all member organisations of the International Federation of Risk and Insurance Management Associations (IFRIMA). A total of 326 specific comments were received from 55 individuals and/or organisations. Each comment was addressed by the Committee, which in many cases resulted in changes to the draft standard. The final document received unanimous approval and was published in November 1995.

The strength of this time consuming and occasionally frustrating process was a final document seen as the product of interdisciplinary discussion and expertise that constituted our collective thinking on “best practice.” We had a wide range of expertise and our members always put forward their views with vigour. This ensured that we had some robust discussions along the way but once agreement was made on the particular word, sentence, paragraph or section, the Committee would move on to the next matter without rancour.

The success of AS/NZS 4360 is due to many individuals. However, as with any group effort, there are always several individuals who make an exceptional difference. I am confident that high quality of the various editions of AS/NZS 4360 and its accompanying handbooks would not have occurred but for the commitment of Dr. Dale Cooper, Professor Jean Cross, Malcomb Buchanan, Janet Gough, Grant Purdy, and Michael Parkinson.

A key feature of AS/NZS 4360 is that it is not limited to traditional insurable risk. What led to the decision to define risk management as a multi-faceted process best facilitated by a multi-disciplinary team?

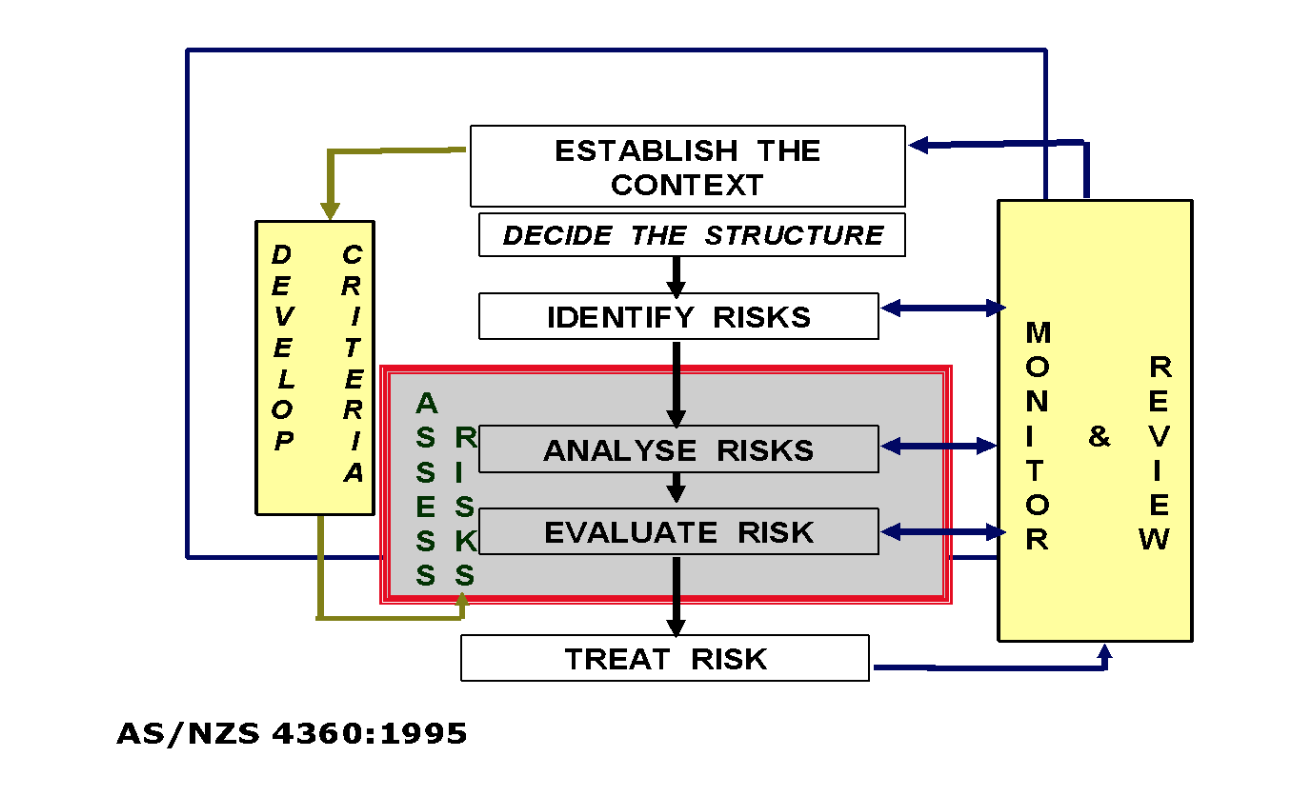

Early on, the following questions dominated our meetings: (i) what is risk; (ii) should risk be limited to insurable risk or was it more encompassing; (iii) how is risk related to quality management; and (iv) how did risk relate to strategic management? The strength of AS/NZS 4360 was the deliberate decision of the Committee that the standard be generic, setting out a process capable of general application to any type of risk. The temptation to confine it to insurance-related corporate risk was firmly rejected by the Committee in favour of it being a generic process for the management of risk, independent of any specific industry or economic sector. Here is the original process as it was issued in 1995:

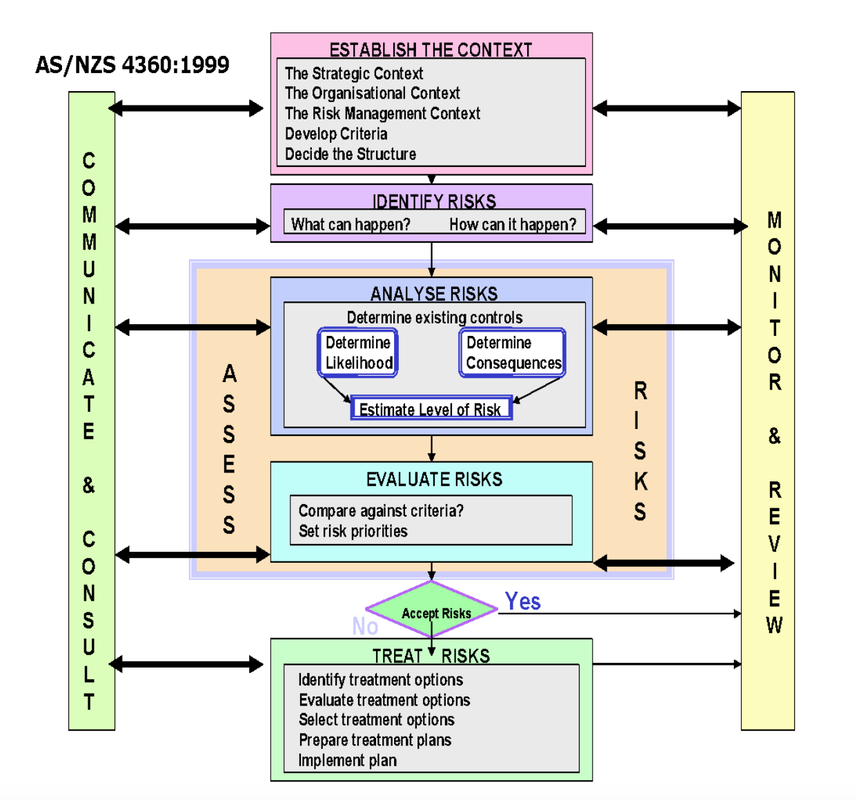

The second edition of AS/NZS 4360 used the same definition of "risk" as the original standard and risk identification remained a separate stage from risk assessment. However, we looked at the work of the Canadians and incorporated the need to “communicate and consult” as the final step in the process. We also sought to clarify the important concept of “establish the context.” This meant adding types of context (strategic, organic, risk management) and the idea of developing applicable criteria for the risk management objective. Here is the more expansive risk management process that was released in 1999:

- Canadian Standards Association Risk Management: Guideline for Decision-Makers CAN/CSA-Q850-1997;

- Japanese Standards Association Draft Risk Management System Standard JIS/TR-Z0001 of November 1997;

- Financial Reporting of Risk - Proposals for a Statement of Business Risk, Institute of Chartered Accountants in England & Wales 1998; and

- Learning about Risk: Choices, Connections and Competencies (July 1998), Canadian Institute of Chartered Accountants.

We introduced a number of important changes as learned from other organizations starting with the work of ISO in 1998 to develop a specific publication on risk management terminology which would be released in 2002 as ISO/IEC Guide 73: 2002 Risk Management – Vocabulary – Guidelines for Use in Standards. Specifically, this work led to our revised definition of “risk” and shift away from a certainty-based approach (“will” in the 1995 and 1999 editions) toward chance and uncertainty as set forth below:

… the chance of something happening that could have an impact on objectives …

Note 1: A risk is often specified in terms of an event or circumstance and the consequences that may flow from it.

Note 2: Risk is measured in terms of a combination of the consequences of an event and their likelihood

Note 3: Risk may have a positive or a negative impact.

Note 4: See ISO/IEC Guide 51, for issues related to safety.

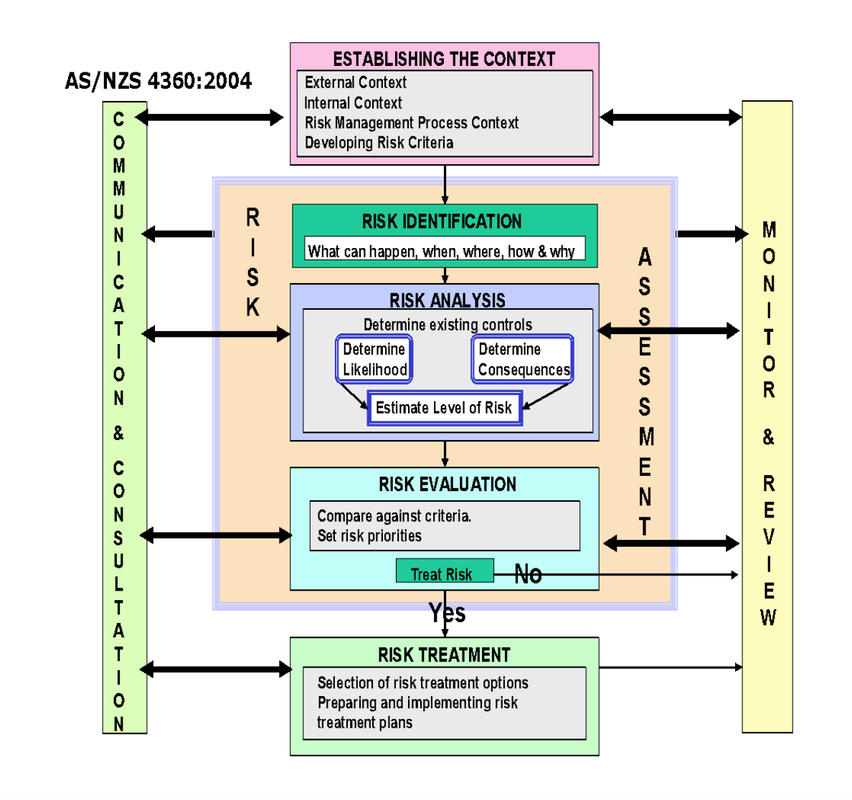

Other changes included broadening the term "risk assessment" to cover risk identification, risk analysis, and risk evaluation.

An area that received much attention was whether we should adopt the ISO concept of probability in lieu of “likelihood” as used in our standard. Many of our members felt that the concept of probability created unnecessary confusion. Ultimately, our committee decided to retain “likelihood" and to add the following discussion to section "1.4 Terminology and translation" in the Standard:

The English-language version of this Standard uses the word “likelihood” to refer to the chance of something happening, whether defined, measured or estimated objectively or subjectively, or in terms of general descriptors (such as rare, unlikely, likely, almost certain), frequencies or (mathematical) probabilities.

ISO/IEC Guide 73 uses the word ‘probability’, in this general sense, to avoid translation problems of ‘likelihood’ in some non-English languages that have no direct equivalent. Because ‘probability’ is often interpreted more formally in English as a mathematical term, ‘likelihood’ is used throughout this Standard, with the intent that it should have the same broad interpretation as ‘probability’ as defined in ISO/IEC Guide 73.

We chose this explanation because AS/NZS 4360 had been translated into several non-English language editions.

A major step forward in the 2004 edition was the inclusion of how to “develop criteria” in the first step of “establishing the context.” Another significant change from previous versions was the removal of the Informative Appendixes from the back of the 2004 edition. The Informative Appendixes had provided examples of likelihood, consequence and risk rating tables and other material to help users introduce risk management to their organisation.

We deleted the appendixes because of two unforeseen problems. First, users tended to just cut and paste them into their process and then find that they needed modification to actually apply and use them within their organisation. Second, auditors would qualify their reports because the tables had been tailored to meet the needs of the organisation and therefore were not identical to what was in the Standard, ignoring the fact that they were advisory.

Here is the revised process known as AS/NZS 4360:2004:

“The Aussies and Kiwis have just finished their latest modification and they’ve done a superb job again! AS/ NZS 4360:2004 was and still remains the clearest and most concise guideline yet published. Its text, only 28 pages, is a model of brevity."

“It is expressed in simple and basic English, free from business jargon. Because its approach is generic, it applies to all forms of organizations. AS/NZS 4360:2004 will become a handy, notated and dog-eared reference on the desk of anyone who practices this discipline. "

“Furthermore, as the standard is generic and requires adaptation to a specific organization, it avoids the complaint that standards are ‘dangerous’ because they can stimulate unneeded legislation and regulations. True, risk management is still evolving, but these guidelines, already in their third evolution, help any organization to begin and modify the process. "

“… These are but minor caveats for a superb statement of the nature and process of our discipline. As I stated before, this document belongs as a working guide for all practicing risk managers: don’t even think of stuffing it into a bookcase.”

I agree with Kloman’s assessment – to me, AS/NZS 4360:2004 met a global need for a generic guide, especially for the adoption of ERM as a risk management process for public and private organizations of all sizes.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed