Part III of our Conversation with Kevin Knight tells the story of how the Australian/New Zealand standard for enterprise risk management became an international standard known as ISO 31000.

In 1996, AS/NZS 4360 became, with some minor modifications, an International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) New Work Item Proposal (NWIP). The IEC is a sister organization of ISO that prepares and publishes international standards for electrical, electronic and related technologies. The original plan was for AS/NZS 4360 to go to the International Standards Organisation (ISO) but because there was no ISO Committee specifically addressing risk management, the NWIP ended up with the IEC in part because its Technical Committee 56 – Dependability (IEC TC 56) was already working on standards for project-based risk management. Founded in 1967, IEC TC 56 is dedicated to the study of dependability management which is the practice of coordinating the reliability, maintainability, supportability, availability and other related aspects of performance.

The IEC Working Group accepted the challenge and placed the NWIP on the agenda for its meeting in Sydney, Australia, in March 1997. The Working Group recognised the need for a top-level document on risk management and thought that the Australian Standard provided a good starting point. The hope was that any resulting paper would become a joint ISO/IEC Standard, once it garnered sufficient support from national standard organisations. A majority of national organisations did approve an IEC TC 56 proposal but there was opposition from France, Canada and the USA, all of whom cast negative votes. The French argued that the proposed document was overly broad for action and that IEC TC 56 lacked the skills to cover all the aspects involved in the proposal. Canada and the USA did not believe the proposal would add value to the existing materials on risk management. The French subsequently lodged a successful appeal with the IEC Committee of Action challenging the vote to accept the NWIP.

These events created a vacuum that was filled in November 1977 by an ad hoc meeting of ISO members interested in risk management. At this meeting, the Japanese Standards Association tried to get agreement that an ISO standard on risk management was needed, and that a draft should be prepared. However, USA, France and Germany continued to oppose the idea. Many of the French and German objections were reasonable but many objections were also based on issues that could be addressed during the drafting process as opposed to precluding any development. Many objections also appeared to be based on insurance and safety matters. The USA suggested the possibility of a “best practices” document being issued by an organisation other than the ISO/IEC. This suggestion was rejected because no such organisation of similar global standing could be identified. The majority proposed a NWIP, but in the end there was no consensus as to whether it should be a Standard, a Technical Report or a Guide. Ultimately, seven of the ten delegations expressed a preference for a Joint ISO/IEC Technical Report or Guide.

Did this debate eventually lead to the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) publishing a vocabulary (Guide 73) on risk management terminology in 2002?

Yes, the vocabulary (Guide 73) came about as a compromise arising from the continued concern of the USA, France and Germany about the potential misuse of any risk management standard by certification bodies. What happened next in the timeline is that in January 1998, the ISO Technical Management Board (TMB) decided in principle to establish an ISO Working Group to develop a specific publication on risk management terminology for ISO and the IEC. Starting with terminology was a consequential decision because it meant that any future work on creating a standard for risk management would need to conform to this terminology guide.

In June 1998, the ISO TMB approved the establishment of a Working Group on Risk Management Terminology comprised of representatives from Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Jamaica, Japan, Norway, Russian Federation, South Africa, Thailand, United Kingdom, and USA along with representatives of the IEC Advisory Committee On Safety (ACOS) and IEC Technical Committee 56 which as I mentioned is focused on dependability management for electric and electronic devices and systems. Following a meeting in Berlin, in October 1999, the Working Group produced a draft document of risk terminology for the ISO TMB to be approved by a vote by the ISO and IEC national associations. The vote was delayed because of difficulties in obtaining support from the IEC ACOS which remained opposed to safety being addressed in a risk management document. A resolution to this impasse was finally achieved and resulted in the 2002 publication of ISO/IEC Guide 73:2002 Risk management - Vocabulary - Guidelines for Use in Standards.

Seven years later, in November 2009, ISO published a revised Guide 73 (vocabulary) and a risk management standard – ISO 31000. How did this come about?

In 2004, Australia, Japan and New Zealand asked ISO to consider adopting AS/NZS 4360:2004 as an international standard. In June 2005, the ISO TMB established a working group representing a wide range of member countries. The working group included representatives from many nations and those representatives had widely divergent backgrounds and involvement in risk. Thus, whereas previous international efforts had tended to involve participants with common risk-related interests (e.g., the safety of people, risks associated with particular sectors, risks arising from particular types of risk source) or particular types of skill (e.g., engineers, risk financers, lawyers, communications experts, managers) the ISO working group comprised a wide range of risk practitioners. The significance of this diversity cannot be underestimated in relation to the subsequent breadth of application of ISO 31000. The ISO standard - ISO 31000:2009 Risk management – Principles and guidelines - was published on November 15, 2009 and adopted four days later by Australia and New Zealand as the replacement for AS/NZS 4360.

While work on ISO 31000 was going on, people realized that the 2002 document on risk management terminology (ISO/IEC Guide 73: 2002 Risk management – Vocabulary – Guidelines for Use in Standards) should be updated at the same time. Consequently, ISO asked the same working group that was writing ISO 31000 to revise the risk management terminology. This led to the revised terminology being published at the same time as ISO 31000 under the name ISO Guide 73: 2009 Risk Management – Vocabulary. Unfortunately, we lost the endorsement of the IEC because various IEC advisory committees continued to object to safety being included within the terminology guide.

I should mention that during the course of developing ISO 31000, a considerable amount of material was developed that specifically related to risk assessment. This material was not included in ISO 31000 because it was considered to be outside the scope of the task assigned to our ISO 31000 working group. Because our working group enjoyed liaison status with IEC TC 56 that had helped develop the guide to risk management terminology, we created a joint working group. This enabled us to pool resources to expand the existing IEC 60300-3-9 Risk Assessment Techniques for Technological Systems into a document that addressed risk assessment techniques across a broader range of activities and was compatible with ISO 31000. The result of this liaison and collaboration was the publication of IEC 31010:2009 Risk management – Risk Assessment Techniques.

In August 2012 and after seeking the views of member organisations, the ISO TMB converted our Working Group into a full Technical Committee (TC) in order to ensure the ongoing development of other risk management documents and the revision of ISO 31000 and its later publication as ISO 31000:2018.

Please give us an overview of ISO 31000 as released in 2009. What are the key attributes?

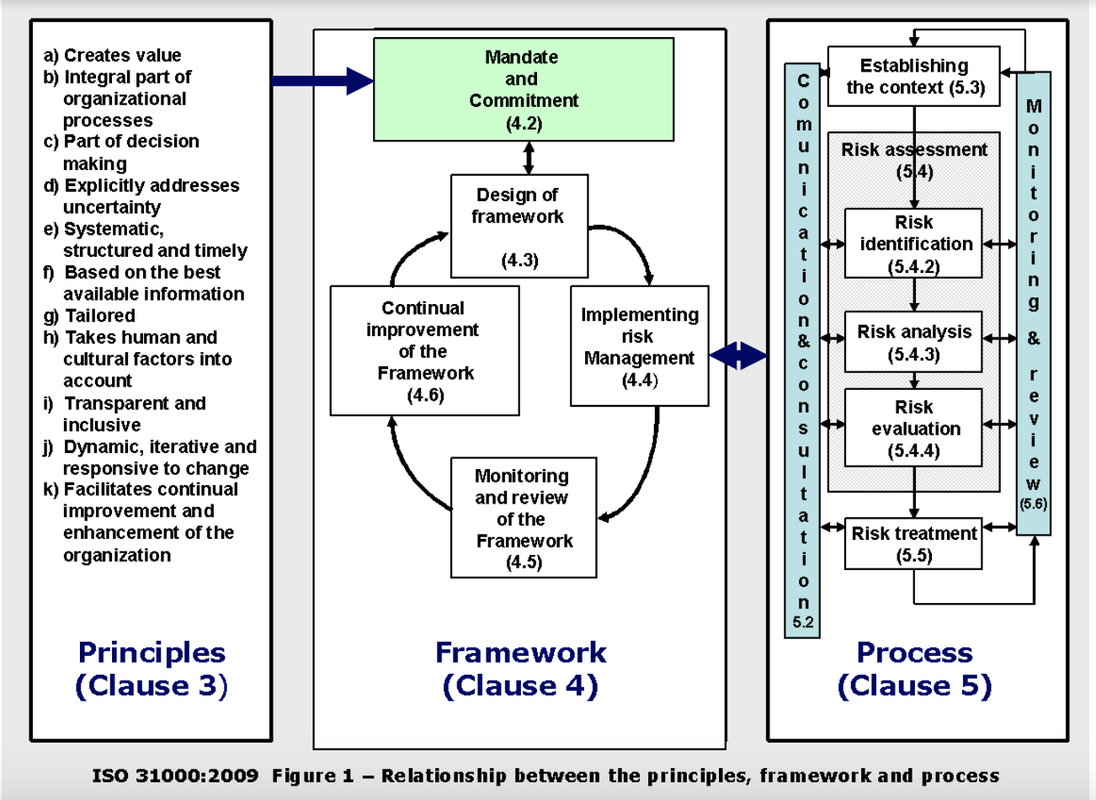

ISO standard 3100 contains five parts and an annex. They are as follows:

1. Scope

2. Terms and definitions

3. Principles

4. Framework

5. Process

Annex. Attributes of enhanced risk management.

Below is an overview of ISO 31000:09, followed by a brief synopsis of each part.

The section entitled “Scope” contains several foundational concepts to keep in mind when using ISO 31000, including as a starting point for devising an ERM framework:

- IS0 31000 provides principles and generic guidelines on risk management.

- ISO 31000 can be used by any public, private or community enterprise, association, group or individual. In other words, ISO 31000 is not specific to any industry or sector.

- ISO 31000 can be applied to any type of risk, whatever its nature and whether having positive or negative consequences.

ISO 31000 provides 29 risk-related definitions and 21 additional definitions are contained in ISO Guide 73: 2009 Risk Management – Vocabulary. Let’s focus on two definitions: risk and risk owner.

Risk is defined as the effect of uncertainty on objectives. As set forth in Note 1, an effect is a deviation from the expected – positive or negative. As set forth in Note 2, objectives can have different aspects such as financial, health and safety, and environmental goals and can apply at different levels such as strategic, organisation-wide, project, product, and process. As set forth in Note 3, risk is often characterised by reference to potential events, consequences, or a combination of these and how they can affect the achievement of objectives. As set forth in Note 4, risk is often expressed in terms of a combination of the consequences of an event or a change in circumstances, and the associated likelihood of occurrence. Finally, as set forth in Note 5, uncertainty is the state, even partial, of deficiency of information related to, understanding or knowledge of, an event, its consequence, or likelihood.

In looking through this definition, keep in mind that a focus on the organization’s objectives is paramount. If the organization’s objectives are unstated or poorly stated, it is difficult, if not impossible, to assess and manage risks. The other significant concept in the Terms and Definitions section is that of risk owner which is defined as a "person or entity with the accountability and authority to manage a risk." The idea here is that no longer should there be orphan risks in organisations with no one being held accountable for how they are managed. The definition does however have three deficiencies.

Firstly, it introduces the concept of the risk owner having "accountability" for decisions with respect to specific risks. This denotes a decision-making role, with others being "responsible" for carrying out the instructions of the risk owner. The problem is the English language blurs the concepts of "accountability" and "responsibility" while other languages often use only one word for both terms. Thus, there is a real need for clear identification within an organisation as to how the decision-maker and the person who carries out their instructions are defined.

Secondly, it allows for an "entity" to be a risk owner, and while management by committee is fashionable it is often characterised by less than clear accountability for decision making. Thirdly, while it can be considered that "authority" includes "resources" it would be preferable for the definition to be specific by the inclusion of "and resources" after authority. In other words, a preferred definition of risk owner would be “person with the accountability, authority and resources to manage a risk.”

Principles

Eleven principles for effective risk management are set out in the standard. This section is a major improvement from the AS/NZS 4360 versions because it clearly sets out the need for senior management to address the principles and develop a mandate and commitment for the inclusion of risk management into the organisation’s overall system of management.

Framework

The framework in Clause 4 of ISO 31000:2009 is not intended to describe a management system; but rather, it is to assist the organization to integrate risk management within its overall management system. Therefore, organizations should adapt the components of the framework to their specific needs.

Development of a tailored framework is crucial if risk management is to be successful. While not explicitly stated in ISO 31000, this allows for a range of risk management processes to be developed within an overarching framework. While each process may apply to specific areas of risk, the processes must remain compatible within the organisation’s management system.

The framework section requires a management mandate and commitment, describes the design of

the framework, and gives guidance on implementing, monitoring and review and continuing improvement of the framework. It is comparable to the management system requirements in ISO 9001 and ISO 14001 but there is no provision for certification of ISO 31000:2009 and nor should there be.

Process

This section calls for the risk management process to become an integral part of management, become embedded in culture and practices, and be tailored to the business processes of the organization. The risk management process includes the five activities of: communication and consultation; establishing the context; risk assessment; risk treatment; and monitoring and review.

Annex

The inclusion of an Annex came from our past experience with seeing how AS/NZS 4360 had wide global use and wanting to spawn discussion among risk practitioners who were striving for continuous improvement. The Annex contains the attributes of enhanced risk management and how a risk management framework can link to decision-making to produce two important outcomes: (i) ensuring that the organisation has a current, correct and comprehensive understanding of its risks and (ii) ensuring that the organisation’s risks are within its risk criteria. The Annex also discusses other subjects including continual improvement, accountability for risks, application of risk management in all decision-making. continual communications, and full integration in the organisation’s governance structure.

You led ISO’s efforts which marked the first time a diverse group of risk practitioners beyond common risk-related interests or sources (e.g., safety) and particular skills or knowledge (e.g., insurance or engineering) had been assembled internationally. What do you remember most about this experience and what gives you the most pride?

The ISO Working Group brought together an interesting cross section of knowledge, skills and experience from all parts of the globe. Only a couple members came from what would be described as a traditional risk management background and the level of formal knowledge and experience in the management of risk ranged from very sophisticated to almost negligible. Added to this mixture was a range of different native languages, whilst the English language was our sole vehicle for communication and collaboration.

A feature of the ISO Working Group was the way the majority of members embraced vigorous debate, like our OB/7 predecessor committee in Australia, but avoided any lasting rancor after the matter was resolved. To succeed, there was often a need for proponents to explain in some detail the concept being proposed so as to enable members to explain the document to their national mirror committee or to facilitate translation of a concept into their native language. As Convener, one of my major tasks was to ensure that the non-English speakers were fully comfortable and could contribute and follow the process.

The fact that such a diverse membership produced a widely accepted document on time and without any major internal political disruptions is the thing that gives me the greatest satisfaction. ISO 31000:2009 went on to become the National Standard on the management of risk in over 50 countries and it was translated into 23 languages. Consequently, those additional countries and organizations that used ISO 31000 – in lieu of formal adoption - was just icing on the cake.

Thinking about your past experiences of leading national and international discussions about risk, what would you say are the most important traits to be developed in successful practitioners of risk management?

A good practitioner should have these qualities:

- a broad understanding of their organization and its objectives as well as a knowledge of the legislation/regulations that impact its operations;

- excellent interpersonal skills to enable interaction with the board and senior management;

- an ability to communicate and consult with people at all levels of the organization;

- an open and enquiring mind and voice that is not afraid to ask challenging questions; and

- the willingness and ability to tell the board and senior management what they need to hear even if it means keeping them awake at night, rather than giving them what they want to hear and is in their “comfort zone.”

What do you think are the major risks that will confront business leaders over the next 25 50 years? How might these risks affect future efforts to standardize the field of risk management?

Effective management of risk is not just a desirable business activity, but is also vital at the national, regional and local levels of government if society is to utilize its resources efficiently and for the general good. I do not see this as something that is going to change in the future. Certainly, there will be all manner of new risks that will have to be managed and that is where ISO 31000 and its future editions will provide the process to assist managers. It must never become prescriptive or a Management System Standard as risk must be managed and not relegated to a tick and flick certification process.

Management of risk is typically seen as a business activity but is increasingly being used to address developing infrastructure that will withstand natural disasters and providing programmes to minimize human suffering. This is not to suggest that it is a panacea for all the ills of society, but if used properly, it empowers people to become more responsible for their actions and helps their community become more resilient.

In closing, I think that the greatest risk of all is to take no risk. Without risk, there is no growth or advancement. All of us are challenged to learn, adapt and to manage risk so as to ensure a successful outcome and that we achieve our highest human potential. That means everyone at all levels of organization and society need to be involved to identify and manage the risk at the most tolerable level. My final thought is that only the person who risks is free.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed