Todd Welch joins us to discuss how insurance and risk management functions best when it is a community of practice developed and nurtured by business leaders and groups who know and trust each other. This first of seven articles on community risk management and captive formation explains the history of insurance and society’s need for better ways to manage and share risk.

Todd is known for promoting trust as a core principle to life, which led to the 2009 publication of his book entitled Trust: How to Put It Back in Business. Todd also collaborated with Vice Adm. John Grossenbacher, former commander of the U.S. Naval Submarine Forces and Paul O’Neill, former Secretary of the U.S. Treasury and Alcoa CEO, to found ZERO, a software platform designed to engage workers in promoting a safer work environment.

IT’S SO SIMPLE: SEVEN STEPS TO CREATING A COMMUNITY CAPTIVE INSURANCE COMPANY

STEP ONE: UNDERSTANDING INSURANCE

“Respect is something we owe everyone we meet. Trust, on the other hand, must be earned.” – John F. McCormick

I’ll share what we’ve learned about Community Risk Management through real-world stories. Complementing these stories are related data and other resources to give you as clear a picture as possible.

Community Risk Management starts with a decision to adopt new thinking everyone in your network can use to improve the speed, quantity, and quality of the business. This includes employees, suppliers, customers, advisors, and believe it or not . . . even competitors.

So, let’s dig into the first step – understanding insurance!

A brief history of insurance.

The year is 1668. The place is Tower Street, London, at the Lloyd’s Café. The news of another ship lost at sea is the main topic of discussion. The ship owners know a loss like this could happen to any of them. Knowing and trusting each other, a small group of ship owners decide that they should band together to share the risk of such a loss in the future. They took a piece of paper and wrote down the details of the next voyage, including the ship’s name, captain, route, expected travel time, and value of the cargo. Underneath the description, they signed their names and notated a percentage of the risk each of them were taking. Each person would receive a portion of the revenue from the owner for taking the risk. They called the signers “underwriters.” This shared risk-taking was the birth of the insurance industry.

This risk model caught on and eventually became what we now know today as Lloyds of London, one of the largest and most sophisticated insurance systems in the world. Looking back, there is no way we could've achieved the incredible benefits of the innovations over the last three and a half centuries without the ability to share risk. Everything from the invention of electricity and airplanes to pharmaceuticals and entertainment could not have been established without insurance. Today we can insure almost anything, even recover from massive natural disasters, because of the global risk-sharing network that has been created over the past few centuries.

However, there has been a downside to all the success. In the process, we have created massive financial institutions that have separated themselves from the local cafés long ago where underwriters and business owners got to know each other and learned to trust each other. We no longer enjoy these relationships and the way they induce positive peer pressure. Any good business leader knows instinctively that collaborative peer pressure is essential to long-term success. In the world of insurance, collaborative peer pressure is essential to ensuring that we prevent losses and that we manage them well after a loss has occurred.

In short, the modern insurance company has become separated from local communities and society in general. Even worse, in some insurance companies, it’s become a badge of honor to take advantage of policyholders when handling their insurance claims. Moreover, at an individual level, lay people are unaware they're part of a community such as State Farm, Liberty Mutual, or MassMutual. These are all peer-owned insurance companies. Nobody seems to know that, and they act like independent financial organizations.

How do we fix this? What we need is an entrepreneurial approach. We believe the Charter Partners System of Community Risk Management, along with a Captive Insurance program, can build a culture that will foster even more significant and prolific innovations. The future lies not with one genius in a garage but in connecting the garages into networks of trusted peers innovating together.

A crisis in insurance.

After 20 years in business, our family insurance agency, Bowers, Schumann and Welch (BS&W), developed an excellent reputation—our clients trusted us. We ranked as one of America’s top 100 brokers. Nearly three out of four small businesses, non-profits, and government organizations in our region were insured through our family business.

Scott Welch, my father, told a famous BS&W story over and over: In the early years of BS&W, a client came into the office to report an accident. His small truck was declared a total loss. There were only a few employees at the time, and Dad was documenting the claim for him. He realized a mistake was made in the original application resulting in the customer having no coverage for his truck.

He hadn’t faced this situation before and felt anxious. What should he do? He excused himself and had a private consultation with his senior partner, Leonard Schumann. After listening to Dad’s story, Leonard said, “Well, Scott, I’m not sure what we are going to do, but I am sure that it starts with telling him the truth.” This story came to exemplify the values of BS&W and continues with Charter Partners, and afterward, everyone knew what to do if they got into a similar situation.

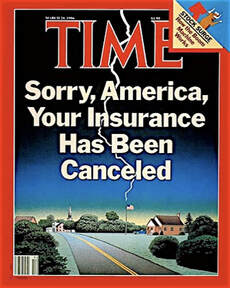

Then, in March 1986, a crisis jeopardized everything he had worked so hard to create. The cover of Time read: “Sorry, America, Your Insurance Has Been Cancelled.” Our clients were in a financial crisis, and some blamed our family business.

What do you do in a crisis?

As the crisis picked up, public schools, one of our key business segments, were hit hard. This crisis caused insurance rates to increase many times the cost of previous years, or policies were unavailable at any price.

In school board meeting after school board meeting, I watched my father defend why the rates had increased so dramatically. The outcome of intense competition, high-interest rates, and overzealous investment between the insurance companies created the crisis. No one in our region, including Dad, had any control over these events. However, BS&W and the Welch family name continued to be in the newspaper, associated with unreasonable insurance rate increases. Public officials threatened to resign due to loss of liability coverage, and these increases caused budgets to be busted. The communities’ anger and frustration boiled over.

Just when most people would run for the hills, Dad did the unexpected: he invited every frustrated public authority to a joint conference at our office. On the surface, you might think him crazy. There was some real tension in the room as the meeting convened. I watched as Dad facilitated a discussion that encouraged everyone to vent their fears. Dad gave the group tools to educate themselves about the facts, and begin to co-design a shared future. Amazingly, he helped them move from crisis to creativity, discovering their answer along the way. In my view, he went from zero to hero; the experience left an indelible impression on me.

As the school boards and education leaders built their confidence in the facts surrounding their situation, they also built mutual trust. They could now determine their future, and they did exactly that. Fourteen public schools came together to form the Warren Hunterdon Insurance Pool (WHIP). WHIP became so successful that two adjoining counties in New Jersey, Morris, and Sussex, asked to join.

However, there were learning experiences along the way. For example, some schools “excused themselves” from participating. Later, we found choosing not to participate is an essential element of group formation. Some people and groups don’t fit the collaboration mold or current standards and politely leave. To our surprise, this consolidation made the core group even stronger. We will talk more about the importance of group formation later.

Conclusion.

Insurance, in general, is a big, messy, complicated beast. At Charter Partners, we believe in getting the right people together, providing industry expertise and knowledge, and creating a sustainable community. We believe that with Community Risk Management and a Captive Insurance program, and simple, consistent systems, we can make a difference in your experience.

Here are the lessons learned from this first section:

- Community Risk Management can restart the innovation engine.

- Tell the truth.

- You can turn adversity into an opportunity if you are willing to listen.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed