We live at a time when humanity is steadily moving away from riskier forms of self-sufficiency to safer and more productive forms of mutual interdependence. This happens only through the evolution of existing systems and models for managing uncertainty. The COVID-19 pandemic is a powerful reminder that improving the rate of learning in a community is essential for evolution to occur.

As summarized well in the above-referenced quote from James Fallows, the COVID 19 pandemic brought to light the challenges of leadership and managing uncertainty in the modern age. Yet this crisis only scratched the surface of the challenges we will face in the future. In March 2021, the U.S. National Intelligence Council released its quadrennial Global Trends Report 2040 which declared that in the coming years and decades, the world will “face more intense and cascading global challenges, ranging from disease to climate change to the disruptions from new technologies and financial crises. These challenges will … often exceed the capacity of existing systems and models.” (Global Trends Report 2040 - A More Contested World, U.S. National Intelligence Council at 1 (March 2021)). In our view, ERM is one of the existing systems and models that must adapt and evolve and leaders in the risk management community can’t be complacent because they think some other field will come along and save the day.

Those of us who are part of the risk management community should look at this moment as an opportunity to make a critical difference. Never has the world needed better leadership that can guide people in how to think, how to debate and disagree, and how to learn from the past while acting on the issues of the present. In short, the world hungers for more people like Edward Jenner and Lady Mary Montague, two heroes in the fight against smallpox, and Albert Schweitzer, the great humanitarian who followed in their footsteps. That is, we need people like Edward Jenner who can develop plans to build solidarity through shared learning opportunities (i.e., the science of vaccine trials) and Lady Mary Montague whose confident advocacy helped people become part of that learning by undergoing the vaccination procedures of her day. And we need people like Albert Schweitzer to teach us that the rate of human progress is affected by the degree to which we respect life, especially life other than our own.

One of the best minds in thinking about how to build better processes and systems for understanding and managing the uncertainty of the current and future pandemics is David Katz. Katz is an American physician and the founding director of the Yale-Griffin Prevention Research Center which focuses on the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases such as obesity and heart disease. From the beginning of the COVID 19 pandemic, Katz understood that the crisis would require leaders to make lots of hard choices in trying to balance all the interests for which they were responsible. What comes after initial steps are taken to “flatten the curve” which only delays but does not prevent a spike in hospital need and mortality, unless maintained until a vaccine is available? For many, messages from leadership seemed to be at one of two extremes - either “everybody back to the world now” which only increases the rate of severe infection and death for those with elevated risk or “hunker in a bunker until there’s a vaccine” which, in turn, disrupts and degrades the flow of goods of services and all the things necessary to help society function and for people maintain their livelihoods.

The better way, as argued by Katz, was for leaders to help their communities learn to make these hard choices together by adopting and using a four part plan:

- Gather and track data on infection, immunity and outcomes continuously to understand risks, prevalence, and needs.

- Differentiate those at high risk for severe infection who must avoid exposure from those at low risk who are most suitable to return to work/the world as we knew it early. Use empirical data to confirm or adjust risk assignments.

- Identify the most essential workforce and economic priorities so those are re-populated first. Identify the overlap between low-risk workers and high priority work as the “first wave” back.

- Sequentially phase in normalcy for the population based on transmission levels, risk level, and identified work priorities.

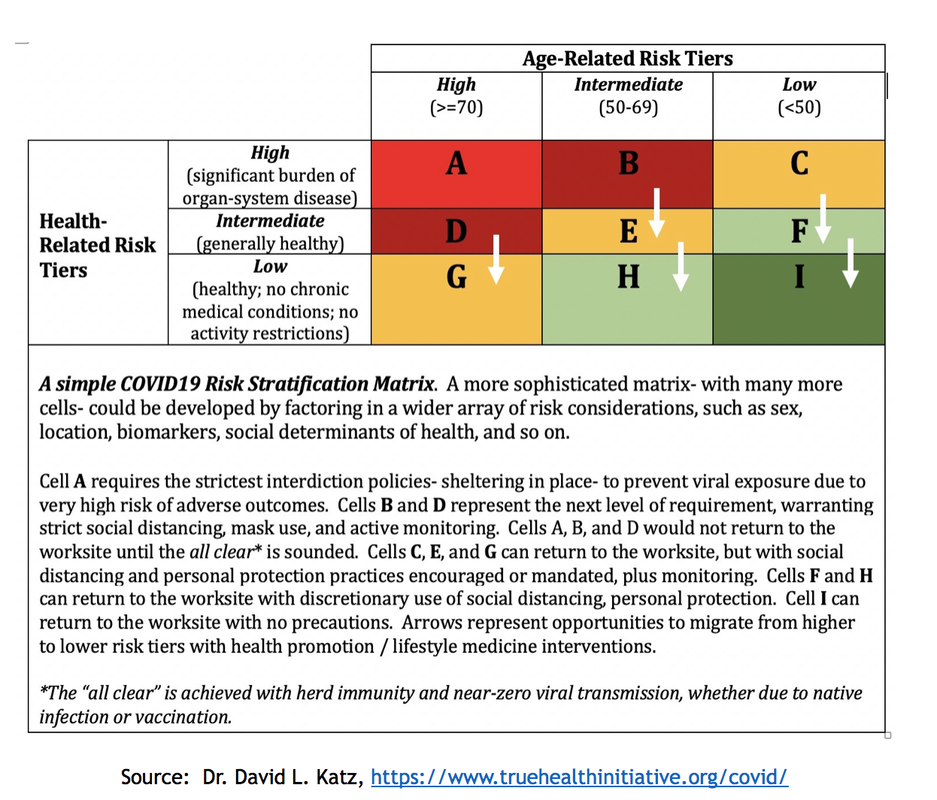

This approach is known as risk stratification and it is designed to help society and people function in a way that maximizes the saving of human lives and the saving of economic livelihoods. Doing so minimizes harm from infection and demands on the medical system while avoiding societal/economic collapse through a phased approach for restoring societal functions and norms.

The beauty of the risk stratification approach is that it helps people learn how to live with some acceptable level of risk and uncertainty. In other words, the pandemic was and is a teachable moment. To flourish, people have to learn how to weigh options, choose between competing priorities, and live with uncertainties that cannot be totally eliminated. This is exactly what Katz’s model of risk stratification is designed to teach. Study for a moment Katz’s model (set forth below) which depicts the risk of a bad outcome from COVID-19 infection in relation to age and general health status. The model also provides a basic template for teaching how and what should be done to promote personal responsibility and collective accountability.

Hopefully, our collective response to the next pandemic will be less haphazard. For that, we will need better leadership that can help organizations function as learning communities. Let everyone know that you hear them (Montague), let everyone know that you care (Schweitzer), and provide a plan to balance the risks of people contracting the virus while addressing other needs such as educating children and helping small businesses survive (Jenner and Katz). In the next section, we will look at the importance of communication as a core element of ERM.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed