We live at a time when humanity is steadily moving away from riskier forms of self-sufficiency to safer and more productive forms of mutual interdependence. The COVID-19 pandemic is yet another test of humanity’s progress in building enterprise-wide approaches for managing risk. In this section, we look at our progress in shaping communication that fosters total engagement.

At the time I am writing this (Summer 2021), navigating the COVID-19 pandemic for American adults is straightforward. Vaccination is readily accessible and once you are vaccinated, you can go about life as you did before the pandemic. Because you are vaccinated, you are unlikely to contract any form of the virus and even if you do, you are unlikely to suffer serious symptoms. In other words, the pandemic has come to resemble the risk of getting a mild case of the flu that you are unlikely to get. Put differently, your chance of getting in a car accident is higher than your chance of getting sick from COVID-19 after a vaccine. Consequently, Americans are gathering once again and engaging in all forms of collective action, be it socializing with family or friends, indoors or outdoors, or filling baseball stadiums that seat 30,000 to 40,000 people.

The same is not true for other parts of the world where vaccine supplies are limited and the vast majority of the population is not yet vaccinated. That raises the question that we began to address in the last section - that is, how can the field of risk management better help leaders make the hard choices that come with trying to balance all the interests for which they are responsible. From the start, we have urged leaders to view the pandemic as a learning opportunity and a teachable moment for increasing our individual and collective skill at weighing options, choosing between competing priorities, and living with uncertainties that cannot be totally eliminated. We also explained how leaders could use risk stratification to create a model or plan that simultaneously explained what should be done individually and collectively.

Successful leaders know that models and plans don’t work unless they are paired with effective communication strategies. Communicating risk management concepts is most effective when it’s visual, acts as a metaphor that explains a complex idea by comparing it to something familiar and provides as narrative that is recognizable to a majority of your audience. One of the best communication tools to help large groups get on the same page with risk analysis and risk management is the Swiss Cheese concept that originated with James T. Reason, a cognitive psychologist and today a professor emeritus at the University of Manchester, England. Using well known examples such as the Challenger shuttle explosion and the Chernobyl nuclear accident, Reason devised a way of communicating how improving human competence can add up to success or result in a catastrophe.

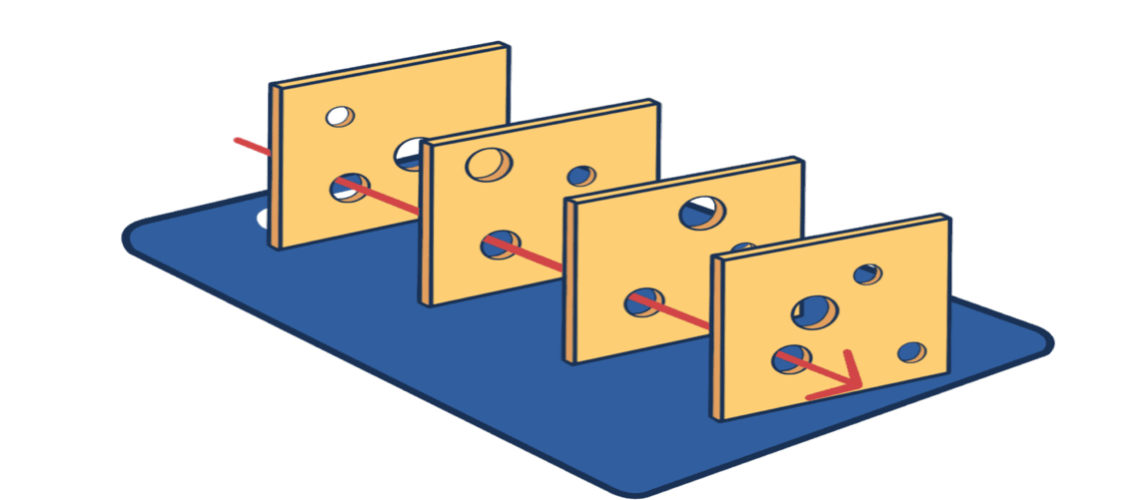

Picture for a moment a block of Swiss cheese that has been separated into multiple slices.

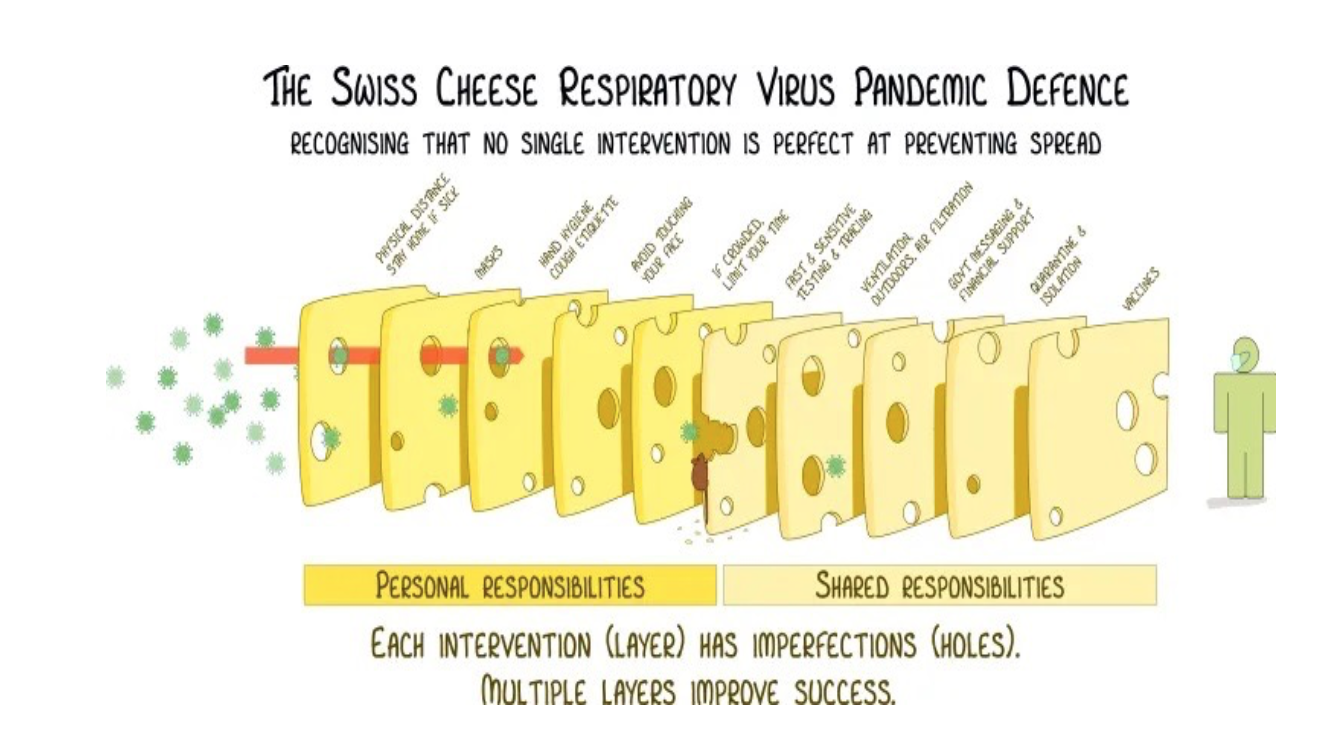

Ian Mackay, a virologist at the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, modified Reason’s Swiss cheese concept as a way to engage more people to change their behavior in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Mackay’s graphic below shows ten cheese slices (See generally S. Roberts, The Swiss Cheese Model of Pandemic Defense, New York Times, (Dec. 5. 2020)). Each slice represents a layer of protection that helps prevent the spread of coronavirus but each slice also has holes or failings and those holes or failings can increase or decrease in size and location depending on the quality and quantity of behavior at each step.

Another message is that each slice or intervention has imperfections. Take masks for example. A good mask reduces the risk that you might infect those around you and it may keep you from inhaling enough virus to become infected. But if the mask is poor-fitting, of lesser quality (e.g., a single piece of cloth), or worn improperly (beneath your nose etc.), the more porous the slice becomes which, in turn, reduces the effectiveness of that particular intervention.

The large bite in the middle of the cheese block represents a mouse who erodes a protective layer by spreading misinformation. The idea is that people who are uncertain about a particular intervention such as mask-wearing might be swayed by someone who is not an expert to not follow that intervention. The graphic teaches us to ignore that “expert” if such person is unqualified and has no relevant experience in protecting our health and safety. Otherwise, we are letting the “misinformation mouse” increase our level of risk.

In short, effective communication is important when dealing with complex ideas. Simple explanations are everything. If people don’t understand what we are asking of them, they are less likely to change their behavior or follow a recommended course of action. Often seeing something is better for learning than describing it in words. Finally, to win hearts and minds, there is no such thing as too much communication.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed