Risk is a seemingly simple word that confounds most organizations when it comes to achieving strategic outcomes. We prefer the word uncertainty. Uncertainty includes strengths, not just weaknesses. Appreciating our strengths helps increase the probability and magnitude of good things happening or what we call positive risk.

- David Cooperrider

Inquiring Into Appreciative Inquiry: A Conversation With David

Cooperrider and Ronald, Fry, Journal of Management Inquiry, 1-15 (2017)

To learn more about how to increase positive deviance, we return to the work of David Cooperrider and Ronald Fry, two professors of organizational behavior at the Weatherhead School of Management at Case Western Reserve University (CWRU). Calling their work Appreciative Inquiry, Cooperrider and Fry have studied positive deviance as a method of change management in organization development for the last 30 years. This block of time and experience has resulted in a robust literature base that describes the methodology for achieving positive deviance and illustrates the approach through case studies ranging from global companies to the United Nations. For a pragmatic, simple, and inspiring introduction to this work, we recommend a short primer entitled Appreciative Inquiry – A Positive Approach to Building Cooperative Capacity (2005). This particular primer is written by Fry and Frank Barrett who, like Fry and Cooperrider, was there at inception during CWRU’s ground-breaking work on Appreciative Inquiry with the Cleveland Clinic.

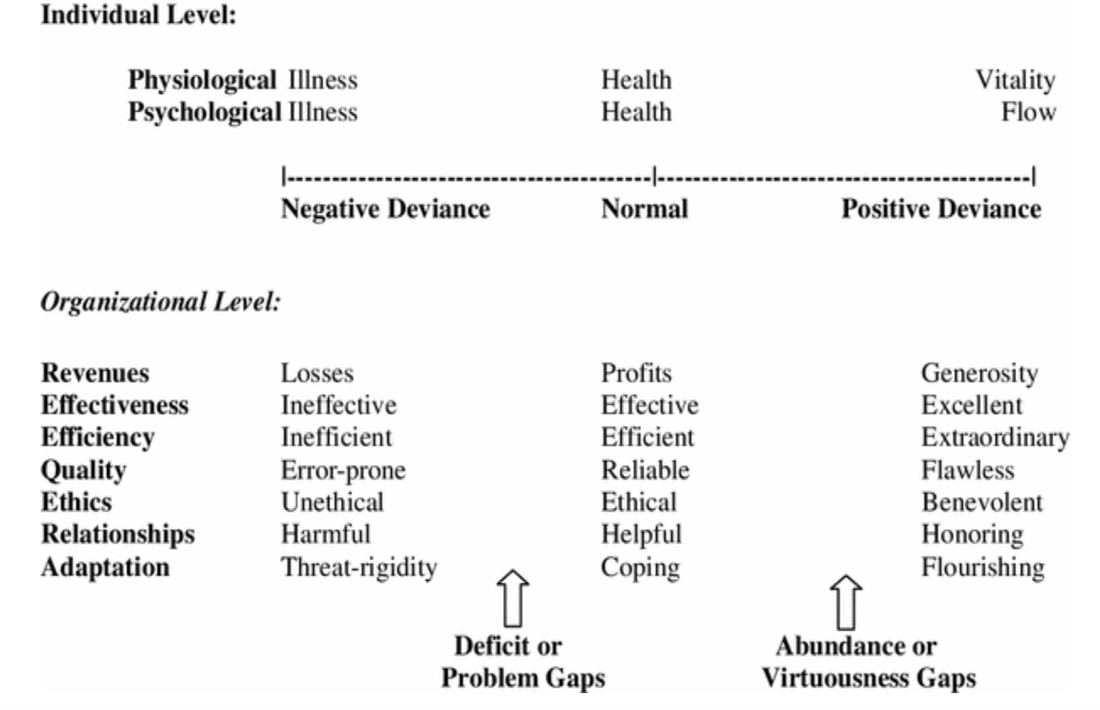

Appreciative Inquiry is consistent with Arie de Geus’ research at Royal Dutch Shell on corporate longevity which focuses on a company functioning as a “living working community” and the importance of engaging the heart and mind of every employee. An inherent obstacle to full company-wide engagement of every employee is the prevalence of a traditional leadership model that emphasizes scientific, objective and rational problem-solving approaches led by leaders from the middle or top of organizations over and above collective and collaborative engagement from the entire organization. The premise of this traditional leadership model is that an organization is a problem to be solved. As depicted in the chart below, this view is incomplete.

The left side of the chart speaks to situations when business leaders respond to a deficit or a problem. We create a project or intervention based on a four-step process of problem identification and analysis, choice of alternatives, development of an action plan, and, ultimately, implementation of the plan. The project is followed by a return to the first step as part of a monitoring/evaluation process. In other words, we develop a picture of what is broken and requires fixing which, in turn, can generate unwanted fear and other negative emotions that if unchecked will cause employees to focus on their self-interests over the common good.

Appreciative Inquiry does not replace the problem-solving method. Instead, it’s an alternative and parallel planning and action model that is better suited to increasing the probability and magnitude of good things happening - positive risk or the right side of the chart. Rather than seeking the root cause of failure, the goal is to seek the root cause of success with the understanding that if all you look for are problems, you will find more problems. In contrast, the goal of Appreciative Inquiry is to use achievements, rather than problems, as the source of organizational learning.

The premise of the Appreciative Inquiry model is that an organization (better described as a living working community) is an innovation to be discovered, not a problem to be solved. The four steps are appreciating the best of what is, envisioning what might be, designing what new actions to take to move forward, and implementing those actions. Similar to the problem-solving cycle, Appreciative Inquiry initiatives require ongoing and regular follow-up to ensure sustainable change.

Chapter eight of Fry and Barrett’s book contains a compelling story about how both types of planning cycles are needed to properly manage risk. A new ownership group buys a one-star hotel and immediately invests $15 million to transform the physical operations with marble floors, new furniture, and updated rooms. Eliminating the deficits or problems on the physical side of the hotel did nothing, however, to change the human side which was plagued by low morale, turf issues, communication gaps, mistrust and bureaucratic breakdowns. Because the general manager was skeptical that anything other than a problem-solving approach (e.g., identify and terminate the low-performing personnel), the intervention was structured so that one set of managers used problem-finding questions to identify causes of poor customer service. The other set of managers focused on discovering moments of exemplary customer service where employees far exceeded their job expectations. When the two groups came together, the first group was lifeless and dispirited while the second group conveyed a compelling and inspiring vision of a four-star hotel. Four years later, through repeated cycles of the Appreciative Inquiry planning model, the hotel achieved four-star status.

The key point of the story is that risk management is ultimately the study of how humans choose in a world of uncertainty. Deterministic problem-solving models are necessary and consistent with basic laws of biology. A living working community – a corporate organism if you will – that can behave more efficiently and more adaptively should have a better chance of survival and reproduction. But efficiency is only one-half of the biological equation; what makes the human race special is that we can embrace and explore the uncertainty of our potential and the environment in which we live. Nobody has complete knowledge of the future; at best we may know probabilities – the potential of a small acorn to fade away or to become a mighty oak.

French aviator and author Antonine de St. Exupery wrote: “If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up men to gather wood, divide the work and give orders. Instead, teach them to yearn for the vast and endless sea.” This sentiment if applied to the risk management community would be transformational. Yes, if asked to help our organizations to build a better boat, we can construct a sea-worthy vessel but if we are inspired to help our communities see the world, who knows what we can accomplish.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed