Because few things are certain, good leaders value expertise and the process of building expert knowledge through fact-based thinking. They embrace the scientific method of gathering, evaluating and analyzing information, and then embracing collaborative review of past experiences and knowledgeable authority for use, study or refutation.

“It is the mark of an educated mind to be able to entertain a thought without accepting it.” - Aristotle

“It is better to learn to struggle with complexity than engage too much in credentialed-based thinking that is based on knowing complicated things.” - Rick Nason, Risk Management Expert and Author of Rethinking Risk Management, Critically Examining Old Ideas and New Concepts (2017)

This article series explores the concept of risk intelligence which we define as the study of how humans choose in a world of uncertainty. The old world is one of traditional risk in which we tend to view organizations as machines that are engaged in learning to how to manage highly repetitive simple or complicated events (a hospital fixing a broken arm (simple risk) or conducting a heart bypass operation (complicated risk)). The new world starts with simple and complicated risk but also is one of complexity in which we view organizations through the metaphor of a living community (not a machine). This living community resembles a distributive network comprised of nodes or individual agents that interact in nonlinear and, therefore, unpredictable ways. In the hospital setting, it’s the challenge of addressing a new disease that might become a pandemic. In the business world, new product development, entering into a joint venture, and engaging in mergers and acquisitions are examples of complex uncertainty.

Studying how an organization functions as a living community brings us to the emerging science about complex adaptive systems. “Complex” means diversity – a wide variety of internal and external elements affecting an organization. “Adaptive” means the capacity to change – to learn from experience. A “system” is a set of connected and interdependent agents that act based on local or surrounding knowledge and conditions. A key aspect of complexity science is that it does not consist of a single theory but rather encompasses many evidence-based theories working together in a multi- and inter-disciplinary manner. After all, a living system learns how to optimize its potential to evolve and that requires a variety of experts (e.g., biologists, chemists, economists, physicists) working together.

Whether the type of uncertainty is simple, complicated or complex, the only way forward is through fact-based thinking and evidence-based decision-making. This requires a commitment to true science and continuous learning. It requires a personal willingness to be open to examining our assumptions and to be self-critical about what we know and don’t know. Science helps us formulate ideas about the preponderance of evidence which enhances our thinking about the most likely outcome of our decision-making. The best we can hope for is to make an informed judgement based on evidence showing a greater probability that something is usually the case. It’s not about proving that something is always the case or never the case. Instead, risk intelligence, especially with complex risk, requires us to develop hypotheses and then constantly test them.

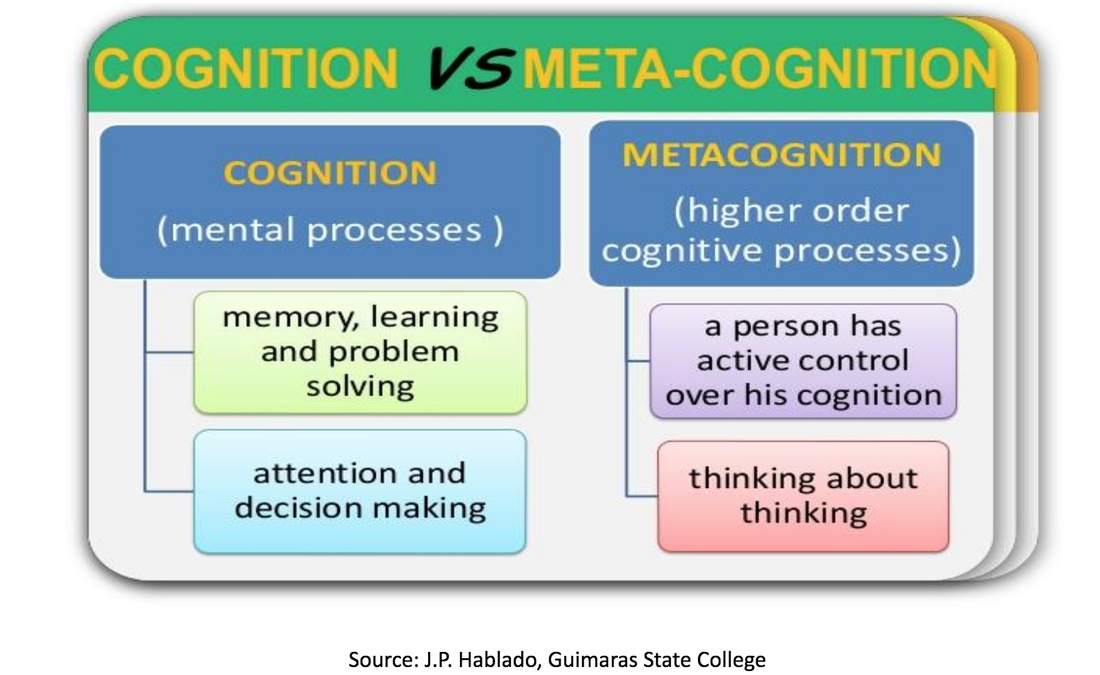

In the previous section, we discussed the inherent risks of cognition which refers to the activities of thinking, knowing, and processing information. Cognitive biases (i.e., heuristics such as the confirmation bias) and emotions hinder our ability to take optimal action in the face of uncertainty. The inherent limitations of our cognitive ability to process information has given rise to the emerging science of metacognition. Again, cognition refers to thinking, knowledge and information-processing. The prefix “meta” means beyond. Therefore, as illustrated in the chart below, metacognition can be defined as cognition about cognition or actively thinking about the way the way we think, learn, and process information.

Considered to be the “father of the field,” Flavell helped turn metacognition into one of the major areas of cognitive developmental research through his study of children and how they learned to develop introspective insight into their own subjective experiences.

Scientific research on the metacognitive skills of business leaders and risk management professionals is in its infancy (See Metacognition in Strategic Decision Making – An Integrative Review and a Research Agenda by A. Najmaei and Z. Sadeghinejad in Decision Making in Behavioral Strategies, Chapter 3, pp 49-81 (Information Age Publishing 2016)).

To help fill the gap, Sydney Finkelstein, a business professor at Dartmouth College, has developed a simple test designed to help business leaders become more self-aware of their own weaknesses and how those weaknesses can contribute to ill-advised decisions.

Finkelstein challenges business leaders to ask themselves four questions on a regular basis:

- How much time do I really spend listening?

- Do I originate most of the ideas?

- Do I often feel like I am the smartest person in the room?

- Do I think of myself as indispensable to my business’s success? (S. Finkelstein, Confident or Overconfident, Four Questions to Ask Yourself, C=Suite Strategies, Wall Street Journal (Feb. 25, 2019)).

Obviously, the goal of these questions is to help a business leader become more self-aware and to understand the importance of becoming skilled in metacognitive behaviors. In the next section, we turn to the challenges of improving metacognition throughout an organization.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed