Because few things are certain, good leaders value expertise and the process of building expert knowledge through fact-based thinking. In the digital age of ubiquitous access to questionable information, nothing might be riskier than organizations making day-to-day decisions in the absence of informed judgment of what constitutes objective reality.

“There is a cult of ignorance in the United States, and there always has been. The strain of anti-intellectualism has been a constant thread winding its way through our political and cultural life, nurtured by the false notion that democracy means that my ignorance is just as good as your knowledge. . . . .I believe that every human being with a physically normal brain can learn a great deal and can be surprisingly intellectual. I believe that what we badly need is social approval of learning and social rewards for learning. We can all be members of the intellectual elite. . . .” - Isaac Asimov, A Cult of Ignorance, Newsweek, Jan 21, 1980

We live at a time of ubiquitous access to news and information that is fueled by technological advancements in connectivity, from 24/7 cable news to the Internet. Looking back at history, each time there has been an advancement in technology, it also has required an advancement in the skills of metacognition and leadership. Take the printing press for example. When it was first created, people thought that the printing press would usher in an age of peace because more people could talk to each other through the written word. Instead, several centuries of religious wars ensued until enough leaders and members of society changed their thinking and advocated for greater separation between church and state.

In the last section, we discussed how organizations in the modern age are faced with increasing levels of uncertainty that can be classified as simple, complicated, or complex. Making good decisions, therefore, requires a commitment to fact-based thinking and the use of subject-matter experts who can help us sift through the relevant evidence, formulate hypotheses, and test them. It also requires increased skill development in metacognition; if something confirms a pre-existing worldview or reinforces self-interest, then it deserves extra scrutiny.

Perhaps, the greatest risk confronting business leaders is helping the people in their organizations keep pace with a volatile and ambiguous world that is increasingly complex. To understand this challenge better, let’s first look at a public health risk that is re-emerging. In 2000, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the leading U.S. public health institute, announced that measles, a childhood disease that still kills more than 100,000 people a year worldwide, had been eradicated in the United States. Almost 20 years later, the disease is back. In early 2019, the Governor of the State of Washington declared a public health emergency and outbreaks were reported in 20 other states.

How is this possible? Put simply, it matters where people get their information and their capacity for fact-finding and critical thinking to construct as accurate view of reality as possible. Vaccinations is but one example of how people can construct the wrong reality (i.e., thinking inoculations cause autism, a claim that is not medically substantiated) by customizing where they get and how they process information Today, the internet is flooded with misinformation questioning the safety of vaccines against measles and other infectious diseases. Further, the paranoia is not bounded by ideology, class, ethnic group or religion. Wealthy professionals in Los Angeles, rural Muslims in pro-Taliban areas of Los Angeles, and Orthodox Jews in New York City have contributed to the resurgence of measles.

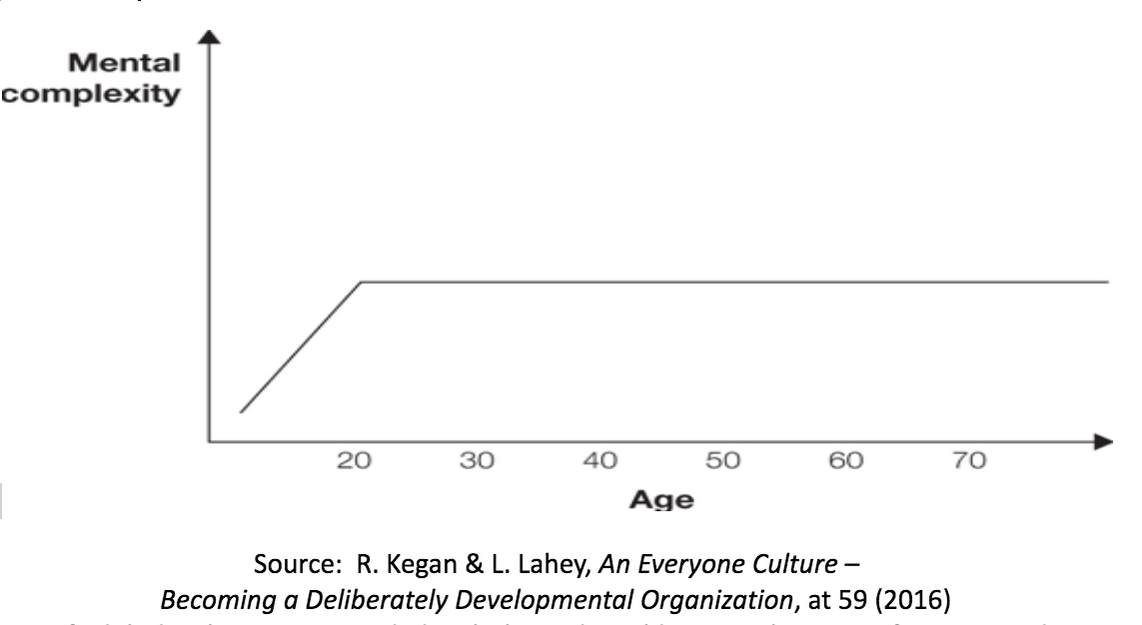

Because everything is done by and through people, the greatest risk is the fit between people’s capacities and the demands made upon them to handle complexity and uncertainty. Hence, increasing the rate of adult development is perhaps the most important strategy to better manage risk. Until the 1980s, the scientific consensus was that human development was static throughout adulthood. That is, the accepted picture of adult development was akin to physical development; human growth was thought to end by our twenties.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed