In an age of increasing uncertainty, the future belongs to those organizations who invest in the development of the skills and abilities of everyone to learn and collaborate in responding to risk, regardless of whether such risk is simple, complicated or complex.

Many people have had the experience of glimpsing the ways in which collaborative work can sometimes produce a much more stunning result than anyone could have done on their own. But for the most part, the whole way in which universities are structured means you have a couple of thousand extraordinarily gifted people all living largely independently of each other, which, if you looked at it as [someone] from another planet, is really absurd. But no one sits around each day and says this is the most ridiculous arrangement I can think of.

Here [at Harvard] you have one of the most privileged situations, thousands of millions of endowment dollars, lovely geographic common space, and you bring all these people together and then build structures that keep them from actually having to work on the really hard challenges of human collaboration. We don’t know how to do this. That gets reflected in lots of other settings as well.” - Interview with Robert Kegan, Harvard Graduate School of Education, March 23, 2000

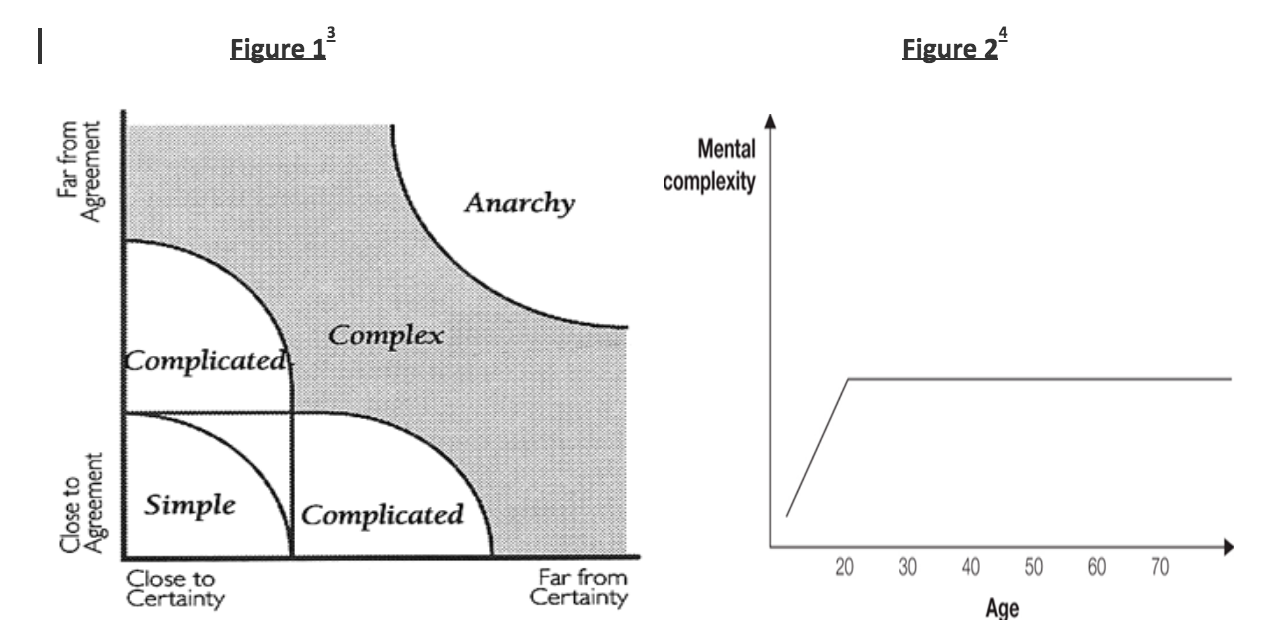

Previous sections have explained that the art of risk management is having an array of approaches for dealing with uncertainty and knowing when to use each approach. We established that uncertainty is best understood as learning how to best operate within three contexts: simple (following a recipe), complicated (sending a rocket to the moon), and complex (raising a child). The challenge for business leaders is that it becomes more difficult to build organizational capacity to manage risk with complicated and complex uncertainty. This task is even more daunting because we are living in a world that is increasingly interdependent which, in turn, is producing more and more uncertainty that is complex. The simple truth is that the only thing business leaders can do in response in the face of increasing complexity is dedicate themselves to building communities of diverse people who are willing to work and willing to work together.

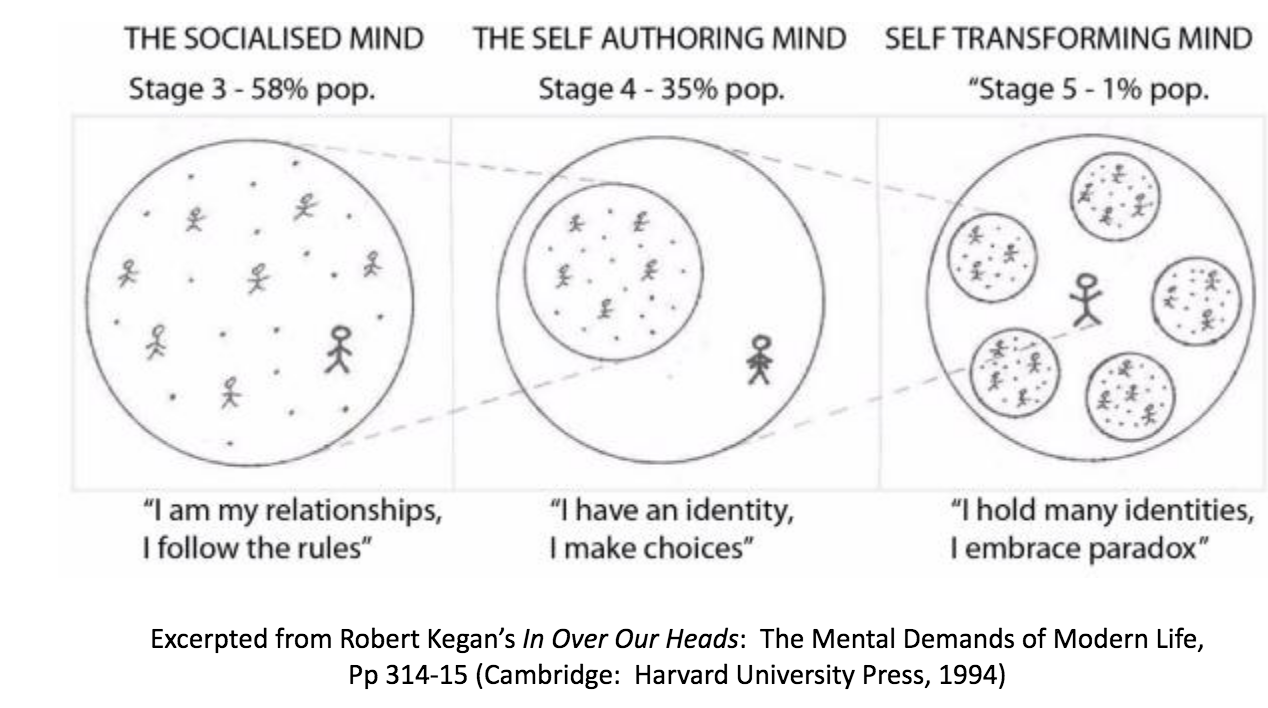

Future sections will focus on the tasks of building networks and how to equip these networks to manage uncertainty. For now, let’s better understand the work of Robert Kegan and why it’s foundational to thinking through how to best to grow people and improve processes to manage risk. Again, as depicted in the Stacey matrix of uncertainty (Figure 1), finding, sharing, and agreeing on what works becomes more difficult as risk becomes more complex. At the same time, much of what is conventional business thinking is based on outdated notions that adults are not capable of growing in skill and capacity to manage complexity (Figure 2).

Keegan’s work focused on developing a framework for adult development that is different than simply learning new things such as adding more skills and knowledge to the container of our mind. Instead, Kegan theorized that adult development is about changing the way we know and understand the world, i.e., changing the actual form of the container or the mind. As an example, prior to Copernicus, humanity thought the earth was the center of the solar system. Copernicus taught us that the sun is at the center and in so doing, human perception of the world changed.

Kegan’s framework operates along the same lines. Advancing to higher stages of adult development is a matter of transformative learning when someone changes not what just he knows but the way he knows. This process begins in childhood and 95% of adults will progress through the first two stages in understanding that the world is more than magic and mystery (first level) or a transactional place in which people are a means to get one’s own needs met (second level). Someone operating at the first level (e.g., a young child) focuses on learning about the world. A second-level person will work in their own best interests and as such will require jobs that have clear boundaries, limited scope, and supervision.

With respect to risk management and the flow and interpretation of information and uncertainty, our focus is on the next three stages of adult development: the socialized, the self-authoring and the self-transforming mind. Each of these levels represents a qualitative shift in human capacity to manage complexity but none of these three levels are inherently better. What matters is the fit between the level and the type of uncertainty confronting the individual and his or her organization.

People with a self-authoring mind develop and follow their own agendas and what information they impart/receive is a function of what they deem others need to or ought to hear to further the agenda or mission put forth by the self-authoring mind. The challenge for the self-authoring mind is avoiding blind spots that arise when this leadership type becomes inattentive to relevant information that is unrequested or seems unimportant to the agenda. Therein lies the difference between the self-authoring mind and the self-transforming mind. A business leader with the latter capacity can step back from his own self-authoring filter and be open to alternative stances, analyses, or agendas.

Supporting others in their personal development to manage uncertainty and complexity is perhaps the most important work of business leadership. As the business world becomes more complex and we are faced with increasing amounts of uncertainty, higher stages of human development are the best resource for managing risk. Kegan summarizes the challenges of managing uncertainty through improved leadership this way:

We need “a new capacity of mind. This new mind must have the ability to author a view of how the organization should run and have the courage to hold steadfastly to that view. But more, the new mind also must be able to step outside its own ideology or framework, observe the framework’s limitations or defects, and author a more comprehensive view - a view it will hold with sufficient tentativeness that it may discover its limitations as well. In other words, the kind of learner {we must] look for in a leader may need to be a person who is making meaning with a self-transforming mind.

Thus, organizations are asking workers who once performed their work successfully with socialized minds – good soldiers – to shift to self-authoring minds. And organizations are asking leaders who once led with self-authoring minds – sure and certain captains – to develop self-transforming minds. In short, organizations are asking for a quantum shift in individual mental complexity.”

- R. Kegan & L. Lahey, An Everyone Culture – Becoming a Deliberately Developmental Organization, at 75 (2016).

Meeting the challenges described Kegan will be addressed in ensuing sections. For now, let’s close this discussion with this recap. Employees with a socialized mind (aka “good soldiers”) with proper support will be able to help manage simple risk and some aspects of complicated risk. This is what we might think of as risk management in the Industrial Age when handling uncertainty was a matter of building best practices through repeated cycles of sensing, categorizing, and responding.

The Information Age led to more complicated problems and the development of good practices through repeated cycles of sense, analyze and respond. This type of leadership is consistent with the self-authoring mind. Leaders with a self-authoring mindset make “good chiefs” because they are agenda-driving, problem-solving, and independent and, as such, can learn to lead teams that devise and administer policies and procedures to manage complicated risk.

The Information Age is now giving way to the Age of Complexity. Uncertainty that is complex requires a skill set that is more akin to probe-sense-collaborate on a response which produces an emergent practice through continuous learning. Employees with a self-transforming mind might be thought as a “village Elder” who is able to see across systems and is able to help the village chiefs to find common ground and to work collaboratively to find and solve problems through interdependence and collaboration. All three types are needed to properly manage enterprise-wide risk which is our next topic.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed